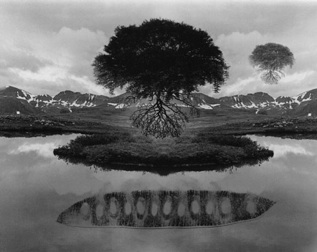

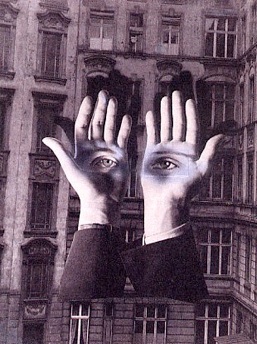

Like Longfellow's little girl with a little curl right in the middle of her forehead, when McNitt's view of life grows dark, things tend to get horrid. Take "Anguish," an unnerving image which is at once stylistically elegant and yet so emotionally-charged that it seems to emerge from a sweat-soaked nightmare. Or "Grief,"an image that captures the sense of a world ripped asunder by death. It's difficult to name another contemporary photographer who can achieve such profound psychological horror without resorting to gothic devices or clichés.

From the richly saturated mock-Cubist "Nude Descending a Guitar Case" to the dazzling blue caustic swirls that lend "Anguish" such stunning originality, McNitt's genius is most evident in the variety and abundance of his themes and techniques. To be sure, within the categories he has demarcated – "All in a Dream," "The Surreal World," "The Darkside," "Nudes," "Dreaming NYC," etc. – there are clusters of stylistically similar images that seem to fit together as snugly as pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.

The "blue images" so prevalent in the "Dream" and "Surreal" galleries have almost become his signature style. Almost. But the brush-like Cubist effect found in such diverse images as "Nude Descending a Guitar Case," "Door at the Edge of the Universe," and "Approaching NYC" is also virtually unique to McNitt. And what of a selective palette that so often seems to favor vibrant reds, ambers, oranges and yellows?

Spend enough time in his galleries, and you will discover that despite its apparent diversity, McNitt's work is unified by an artistic sensibility that is fascinated, if not obsessed, with the inner workings of the human mind. What makes him so unusual is that McNitt explores our most desperate emotions with the same intensity that he brings to celebrating the beauty of the physical world.

As a result, his work is becoming increasingly collectable. McNitt can be found in the personal collections of Ralph Lauren, Tommy Hilfiger and Ted Turner. The Librairie Maritime et Outre Mer in Paris mounted a massive retrospective of his marine photography in 2000 and his sailing photos are now in the permanent collections of nearly a dozen museums around the world. Among his recent work, some of the images most popular with corporate and private collectors include "Umbrage,""Fantasm,""Carnevale di Venezia,""Time Warp," and "Serenity.”

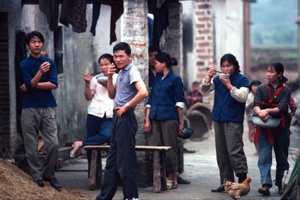

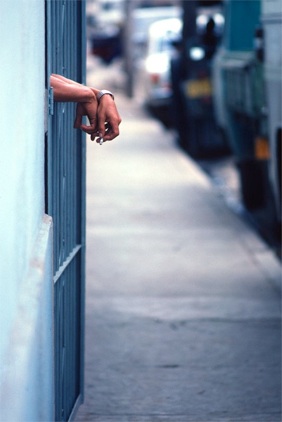

In the end, whether working as a photojournalist, as in the unique marine aerial"Tall Boy" and the haunting 1978 photo of "Hands" in Santiago, Cuba, or creating fine-arts composites such "Falling," "Aguish," "Grief," "Pepper," and "Shutter Bird," McNitt's greatest gift is the ability to reveal the iconic essence of his subject.